- Thou Shalt Honor RFC-822, Or Not Read Email At All (08 Nov 2009)

- And... Action! (Part 3, 19 Sep 2009)

- Noch freie Kegeltermine! (19 Sep 2009)

- And... Action! (Part 2, 08 Sep 2009)

- 10 on Monday, 100 on Wednesday (02 Sep 2009)

- "This software will crash Real Soon Now™. Promise!" (02 Sep 2009)

- How to Detect Mergers & Acquisitions in Code (01 Sep 2009)

- And... Action! (31 Aug 2009)

- A package riddle, part IV (28 Aug 2009)

- Paradigms of Artificial Intelligence Programming (25 Aug 2009)

- A package riddle, part III (22 Aug 2009)

- A package riddle, part II (20 Aug 2009)

- A package riddle (19 Aug 2009)

- STEP files for the masses (29 Jul 2009)

- What's in a name? (25 Jul 2009)

- TWiki, KinoSearch and Office 2007 documents (20 Jul 2009)

- I'd rather take it nice and slow - disabling 3D acceleration in CoCreate Modeling (15 Jul 2009)

- Java-Forum Stuttgart (06 Jul 2009)

- Common Lisp in CoCreate Modeling (20 Jun 2009)

- head replacement on Windows (16 Jun 2009)

- Sightrunning in Milan (12 Jun 2009)

- Echt einfach, Alter! (09 Jun 2009)

- European Lisp Symposium: Geeks Galore! (07 Jun 2009)

- European Lisp Symposium 2009: Keynote (03 Jun 2009)

- European Lisp Symposium 2009 (30 May 2009)

- Speeding through the crisis (22 Apr 2009)

- Reasons To Admire Lisp (part 1) (16 Apr 2009)

- mod_ntlm versus long user names (06 Mar 2009)

Thou Shalt Honor RFC-822, Or Not Read Email At All (08 Nov 2009)

- Create a

tempfolder on the IMAP server - Move all messages from the

Inboxto thetempfolder - With all inbox messages out of the way, hit Thunderbird's "Get Mail" button again.

telnet int-mail.ptc.com 143 . login cbrod JOSHUA . select INBOX . fetch 1:100 flagsSurprisingly, IMAP still reported 17 messages, which I then deleted manually as follows:

. store 1:17 flags \Deleted . expunge . closeAnd now, finally, the error message in Thunderbird was gone. Phew. In hindsight, I should have kept those invitation messages around to find out more about their RFC-822 compliance problem. But I guess there is no shortage of meeting invitations in an Outlook-centric company, and so there will be more specimens available for thorough scrutiny

And... Action! (Part 3, 19 Sep 2009)

Let me explain.

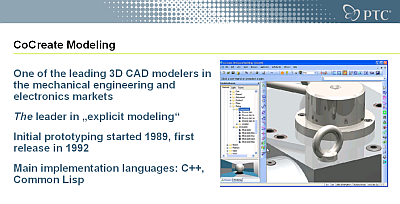

In the 80s, our 2D CAD application ME10 (now: CoCreate Drafting)

had become extremely popular in the mechanical

engineering market. ME10's built-in macro language was a big success factor.

Users and CAD administrators counted on it to configure their local installations,

and partners wrote macro-based extensions to add new functionality - a software

ecosystem evolved.

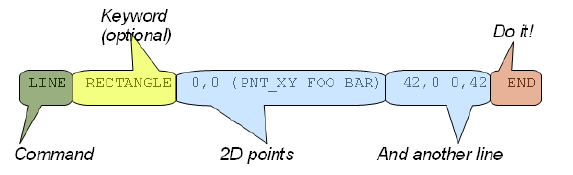

A typical macro-language command looked like this:

Let me explain.

In the 80s, our 2D CAD application ME10 (now: CoCreate Drafting)

had become extremely popular in the mechanical

engineering market. ME10's built-in macro language was a big success factor.

Users and CAD administrators counted on it to configure their local installations,

and partners wrote macro-based extensions to add new functionality - a software

ecosystem evolved.

A typical macro-language command looked like this:

Users didn't have to type in the full command, actually. They could start by typing in

Users didn't have to type in the full command, actually. They could start by typing in LINE

and hitting the ENTER key. The command would prompt for more input and provide hints in the

UI on what to do next, such as selecting the kind of line to be drawn, or picking points

in the 2D viewport (the drawing canvas). The example above also illustrates that commands

such as LINE RECTANGLE could loop, i.e. you could create an arbitrary amount of rectangles;

hence the need to explicitly END the command.

Essentially, each of the commands in ME10 was a domain-specific mini-language,

interpreted by a simple state machine.

The original architects of SolidDesigner (now known as CoCreate Modeling)

chose Lisp as the new extension and customization language, but they also wanted

to help users with migration to the new product. Note, however, how decidedly un-Lispy ME10's

macro language actually was:

- In Lisp, there is no way to enter just the first few parts of a "command"; users always have to provide all parameters of a function.

- Lisp functions don't prompt.

- Note the uncanny lack of parentheses in the macro example above.

- Define a special class of function symbols which represent commands

(example:

extrude). - Those special symbols are immediately evaluated anywhere

they appear in the input, i.e. it doesn't matter whether they appear inside

or outside of a form. This takes care of issue #3 above, as you no longer

have to enclose

extrudecommands in parentheses. - Evaluation for the special symbols means: Run the function code associated with the symbol. Just like in ME10, this function code (which we christened action routine) implements a state machine prompting for and processing user input. This addresses issues #1 and #2.

define-symbol-macro yet. And thus,

CoCreate Modeling's Lisp evaluator extensions were born.

To be continued...

Noch freie Kegeltermine! (19 Sep 2009)

Zu essen gab es in jenem Restaurant kroatisch-serbisch-italienisch-schwäbisches Crossover, und für Unterhaltung war auch gesorgt:

And... Action! (Part 2, 08 Sep 2009)

No, we don't need contrived constructs like (print extrude) to show that

No, we don't need contrived constructs like (print extrude) to show that

extrude is somehow... different from all the other kids. All we need is a simple experiment.

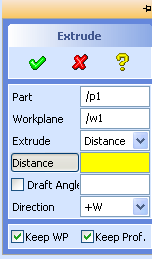

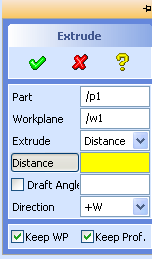

First, enter extrude in

CoCreate Modeling's user input line: The Extrude dialog

unfolds in all its glory, and patiently awaits your input.

Now try the same with print: All you get is an uncooperative

"Lisp error: The variable PRINT is unbound". How disappointing.

But then, the behavior for print is expected, considering the usual

evaluation rules for Common Lisp,

particularly for symbols. As a quick reminder:

- If the symbol refers to a variable, the value of the variable is returned.

- If the symbol refers to a function and occurs in the first position of a list, the function is executed.

extrude & friends belong to the symbol jet-set in CoCreate Modeling. For them,

the usual evaluation rules for functions don't apply (pun intended).

Using symbol properties

as markers, they carry a backstage pass and can party anywhere.

For members of the extrude posse, it doesn't really matter if you use them as an

atom, in the first position of a list, or anywhere else: In all cases, the function which

they refer to will be executed right away - by virtue of an extension to the evaluator

which is unique to CoCreate Modeling's implementation of Common Lisp.

You can create such upper-class symbols yourself - using a macro called defaction.

This macro is also unique to CoCreate Modeling. Functions

defined by defaction are called, you guessed it, action routines.

But why, you ask, would I want such a feature, particularly if I know that it breaks with

established conventions for Lisp evaluation?

Well, precisely because this feature breaks with the established rules.

To be continued...

10 on Monday, 100 on Wednesday (02 Sep 2009)

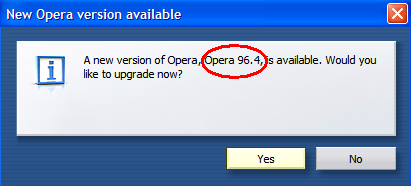

Now, that's rapid development!

PS: Yes, I know, this is old hat, but the message still gave me a good chuckle

PS: Yes, I know, this is old hat, but the message still gave me a good chuckle

"This software will crash Real Soon Now™. Promise!" (02 Sep 2009)

Fortunately, CoCreate Modeling has always had pretty elaborate crash handling mechanisms. Whenever an unexpected exception occurs, a top-level crash handler catches it, pops up a message describing the

problem, causes the current operation to be undone, restores the 3D model to a (hopefully) consistent

state, and returns the user to the interactive top-level loop so that s/he can save the

model before restarting.

Over time, we taught our crash handler to deal with more and more critical situations. (Catching stack overflows and multithreading scenarios are particularly tricky.) Hence, users rarely lose data in

CoCreate Modeling even if some piece of code crashes. Which pretty much obviates the need

for the proposed clairvoyance module.

Fortunately, CoCreate Modeling has always had pretty elaborate crash handling mechanisms. Whenever an unexpected exception occurs, a top-level crash handler catches it, pops up a message describing the

problem, causes the current operation to be undone, restores the 3D model to a (hopefully) consistent

state, and returns the user to the interactive top-level loop so that s/he can save the

model before restarting.

Over time, we taught our crash handler to deal with more and more critical situations. (Catching stack overflows and multithreading scenarios are particularly tricky.) Hence, users rarely lose data in

CoCreate Modeling even if some piece of code crashes. Which pretty much obviates the need

for the proposed clairvoyance module.

How to Detect Mergers & Acquisitions in Code (01 Sep 2009)

And... Action! (31 Aug 2009)

print and

CoCreate Modeling commands such as extrude differ and how they

interact, you've come to the right place.

Usually, I call a dialog like this: (set_pers_context "Toolbox-Context" function) Or like this: function As soon as I add parentheses, however, the "ok action" will be called: (function)

When highway45 talks of "functions" here, he actually means commands like

When highway45 talks of "functions" here, he actually means commands like extrude or turn. So, (set_pers_context "Toolbox-Context" extrude)? Really? Wow!

set_pers_context is an internal CoCreate Modeling function dealing with

how UI elements for a given command are displayed and where. I was floored -

first, by the fact that an end user found a need to call an internal function like this,

and second, because that magic incantation indeed works "as advertised" by highway45.

For example, try entering the following in CoCreate Modeling's user input line:

(set_pers_context "Toolbox-Context" extrude)Lo and behold, this will indeed open the

Extrude dialog, and CoCreate Modeling

now prompts for more input, such as extrusion distances or angles.

What's so surprising about this, you ask? If you've used CoCreate Modeling for a while,

then you'll know that, as a rule of thumb, code enclosed in parentheses won't prompt

for more input, but will instead expect additional parameters in the command line itself.

For example, if you run (extrude) (with parentheses!) from the user input line, Lisp will

complain that the parameter "DISTANCE is not specified". But in highway45's example, there

clearly was a closing parenthesis after extrude, and yet the Extrude command started to

prompt!

So is set_pers_context some kind of magic potion? Try this:

(print extrude)The Extrude dialog opens and prompts for input! Seems like even

print has

magic powers, even though it's a plain ol' Common Lisp standard function!

Well, maybe there is something special about all built-in functions? Let's test this out and

try a trivial function of our own:

(defun foobar() 42) (foobar extrude)Once more, the dialog opens and awaits user input! So maybe it is neither of

set_pers_context, print or foobar that is magic - but instead extrude.

We'll tumble down that rabbit hole next time.

To be continued...

A package riddle, part IV (28 Aug 2009)

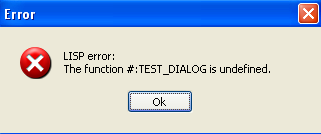

(defun test() (test_dialog)) (in-package :clausbrod.de) (use-package :oli) (sd-defdialog 'test_dialog :ok-action '(display "test_dialog"))In part 3 of this mini-series, we figured out that the #: prefix indicates an uninterned symbol - and now we can solve the puzzle! Earlier, I had indicated that

sd-defdialog automatically exports dialog

names into the default package. To perform this trick, somewhere in the bowels of

the sd-defdialog macro, the following code is generated and executed:

(shadowing-import ',name :cl-user) ;; import dialog name into cl-user package (export ',name) ;; export dialog name in current package (import ',name :oli) ;; import dialog name into oli package (export ',name :oli) ;; export dialog name from the oli packageAs a consequence, the dialog's name is now visible in three packages:

- The default package (

cl-user) - Our Lisp API package (

oli) - The package in which the dialog was defined (here:

clausbrod.de)

shadowing-import inserts each of symbols into package as an internal symbol, regardless of whether another symbol of the same name is shadowed by this action. If a different symbol of the same name is already present in package, that symbol is first uninterned from package.That's our answer! With this newly-acquired knowledge, let's go through our code example one more and final time:

(defun test() (test_dialog))Upon loading this code, the Lisp reader will intern a symbol called

test_dialog into the current (default) package. As test_dialog has not

been defined yet, the symbol test_dialog does not have a value; it's just

a placeholder for things to come.

(in-package :clausbrod.de) (use-package :oli)We're no longer in the default package, and can freely use

oli:sd-defdialog without

a package prefix.

(sd-defdialog 'test_dialog :ok-action '(display "test_dialog"))

sd-defdialog performs (shadowing-import 'test_dialog :cl-user),

thereby shadowing (hiding) and uninterning the previously interned test_dialog symbol.

Until we re-evaluate the definition for (test), it will still refer to the

old definition of the symbol test_dialog, which - by now - is a) still without

a value and b) uninterned, i.e. homeless.

Lessons learned:

- Pay attention to the exact wording of Lisp error messages.

- The Common Lisp standard is your friend.

- Those Lisp package problems can be pesky critters.

(test) function would have saved

us all that hassle.

Phew.

Paradigms of Artificial Intelligence Programming (25 Aug 2009)

loop macro,

and ever since then, I knew I had to buy the book. The code contains a good amount of

Lisp macrology, and yet it is clear, concise, and so easy to follow. You can read it

like a novel, from cover to back, while sipping from a glass of pinot noir.

Impressive work.

If you've soaked up enough

Common Lisp to roughly know what lambda and defmacro do, this is the kind of

code you should be reading to take the next step in understanding Lisp. This is also

a brilliant way to learn how to use loop, by the way.

I can't wait to find out what the rest of the book is like!

Update 9/2013: Norvig's (How to Write a (Lisp) Interpreter (in Python))

is just as readable and inspirational as the loop macro code. Highly recommended.

A package riddle, part III (22 Aug 2009)

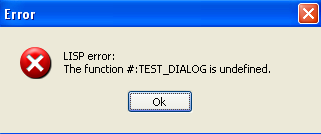

(defun test() (test_dialog)) (in-package :clausbrod.de) (use-package :oli) (sd-defdialog 'test_dialog :ok-action '(display "test_dialog"))Load the above code, run

(test), and you'll get:

In CoCreate Modeling, the

sd-defdialog macro automatically exports the name of the new

dialog (in this case, test_dialog) into the default package. Hence, you'd expect that

the function (test), which is in the default package, would be able to call that dialog!

Astute readers (and CoCreate Modeling's Lisp compiler) will rightfully scold me for using

(in-package) in the midst of a file. However, the error doesn't go away if you split up

the above code example into two files, the second of which then properly

starts with (in-package). And in fact, the problem originally manifested itself in a

multiple-file scenario. But to make it even easier for readers to run the test themselves,

I just folded the two files into one.

Lisp actually provides us with a subtle hint which I ignored so far: Did you notice

that the complaint is about a symbol #:TEST_DIALOG, and not simply TEST_DIALOG?

The #: prefix adds an important piece to the puzzle. Apparently, Lisp thinks

that TEST_DIALOG is not a normal symbol,

but a so-called uninterned symbol. Uninterned symbols are symbols which don't

belong to any Lisp package - they are homeless. For details:

- Creating Symbols (from "Common Lisp the Language", 2nd edition)

- Programming in the Large: Packages and Symbols (from Peter Seibel's excellent "Practical Common Lisp")

- The Complete Idiot's Guide to Common Lisp Packages

- Potting Soil: Colons continued - uninterned symbols

TEST_DIALOG turned into an uninterned symbol. We would have expected it to

be a symbol interned in the clausbrod.de package, which is where the dialog is defined!

Those who are still with me in this series will probably know where this is heading.

Anyway - next time, we'll finally

solve the puzzle!

A package riddle, part II (20 Aug 2009)

(defun test() (test_dialog)) (in-package :clausbrod.de) (use-package :oli) (sd-defdialog 'test_dialog :ok-action '(display "test_dialog"))Here is what happens if you save this code into a file, then load the file into CoCreate Modeling and call the

(test) function:

"The function #:TEST_DIALOG is undefined"? Let's review the code so that you can understand why I found this behavior surprising. First, you'll notice that the function

test is defined in the default Lisp package.

After its definition, we switch into a different package (clausbrod.de), in

which we then define a CoCreate Modeling dialog called test_dialog.

The (test) function attempts to call that dialog. If you've had any exposure with

other implementations of Lisp before, I'm sure you will say: "Well, of course the system

will complain that TEST_DIALOG is undefined! After all, you define it in package

clausbrod.de, but call it from the default package (where test is defined).

This is trivial! Go read

The Complete Idiot's Guide to Common Lisp Packages

instead of wasting our time!"

To which I'd reply that sd-defdialog, for practical reasons I may go into in a future blog

post, actually makes dialogs visible in CoCreate Modeling's default package. And since

the function test is defined in the default package, it should therefore have

access to a symbol called test_dialog, and there shouldn't be any error messages, right?

To be continued...

A package riddle (19 Aug 2009)

(defun test() (test_dialog)) (in-package :clausbrod.de) (use-package :oli) (sd-defdialog 'test_dialog :ok-action '(display "test_dialog"))

test.lsp, then load the file

into a fresh instance of CoCreate Modeling. Run the test function by entering (test) in

the user input line. Can you guess what happens now? Can you explain it?

To be continued...

STEP files for the masses (29 Jul 2009)

;; (C) 2009 Claus Brod ;; ;; Demonstrates how to convert models into STEP format ;; in batch mode. Assumes that STEP module has been activated. (in-package :clausbrod.de) (use-package :oli) (export 'pkg-to-step) (defun convert-one-file(from to) (delete_3d :all_at_top) (load_package from) (step_export :select :all_at_top :filename to :overwrite) (undo)) (defun pkg-to-step(dir) "Exports all package files in a directory into STEP format" (dolist (file (directory (format nil "~A/*.pkg" dir))) (let ((filename (namestring file))) (convert-one-file filename (format nil "~A.stp" filename)))))To use this code:

- Run CoCreate Modeling

- Activate the STEP module

- Load the Lisp file

- In the user input line, enter something like

(clausbrod.de:pkg-to-step "c:/allmypackagefiles")

*.pkg) file in the specified directory, a STEP file will be generated in the

same directory. The name of the STEP file is the original filename with .stp appended to it.

In pkg-to-step, the code iterates over the list of filenames returned from

(directory). For each package file, convert-one-file is called, which performs

the actual conversion:

| Step | Command |

|---|---|

| Delete all objects in memory (so that they don't interfere with the rest of the process) | delete_3d |

| Load the package file | load_package |

| Save the model in memory out to a STEP file | step_export | Revert to the state of affairs as before loading the package file | undo |

delete_3d, load_package,

step_export and undo. (These are the kind of commands which are captured in a recorder

file when you run CoCreate Modeling's recorder utility.) Around those commands, we use

some trivial Common Lisp glue code - essentially, dolist over

the results of directory. And that's all, folks  Astute readers will wonder why I use

Astute readers will wonder why I use undo after the load operation rather than delete_3d

the model. undo is in fact more efficient in this kind of scenario, which is

an interesting story in and of itself - and shall be told some other day.

What's in a name? (25 Jul 2009)

| Official name | Colloquial | Versions | When |

|---|---|---|---|

| HP PE/SolidDesigner | SolidDesigner | 1-7 | 1992-1999 |

| CoCreate SolidDesigner | SolidDesigner | 8-9 | 2000-2001 |

| CoCreate OneSpace Designer Dynamic Modeling | ? | 11 | 2001-2002 |

| CoCreate OneSpace Designer Modeling | OSDM | 11.6-14 | 2002-2006 |

| CoCreate OneSpace Modeling | OneSpace Modeling | 15 | 2007 |

| PTC CoCreate Modeling | CoCreate Modeling | 16 and later | 2008- |

- HP PE/SolidDesigner (colloquially: SolidDesigner)

- CoCreate SolidDesigner (colloquially: SolidDesigner)

- PTC CoCreate SolidDesigner (colloquially: SolidDesigner)

SolidDesigner.exe  Anyway - I'll have to admit that I start to like "CoCreate Modeling" as well. It's reasonably

short, simple to remember, alludes to what the product does, and it reminds users of our

past as CoCreate - which is a nice nostalgic touch for old f*rts like me who've

been with the team for almost two decades now...

Anyway - I'll have to admit that I start to like "CoCreate Modeling" as well. It's reasonably

short, simple to remember, alludes to what the product does, and it reminds users of our

past as CoCreate - which is a nice nostalgic touch for old f*rts like me who've

been with the team for almost two decades now...

TWiki, KinoSearch and Office 2007 documents (20 Jul 2009)

.docx, .pptx and .xlsx,

i.e. the so-called "Office OpenXML" formats. That's a pity, of course, since

these days, most new Office documents tend to be provided in those formats.

The KinoSearch add-on doesn't try to parse (non-trivial) documents

on its own, but rather relies on external helper programs which extract

indexable text from documents. So the task at hand is to write such

a text extractor.

Fortunately, the Apache POI project just released

a version of their libraries which now also support OpenXML formats, and

with those libraries, it's a piece of cake to build a simple text extractor!

Here's the trivial Java driver code:

package de.clausbrod.openxmlextractor;

import java.io.File;

import org.apache.poi.POITextExtractor;

import org.apache.poi.extractor.ExtractorFactory;

public class Main {

public static String extractOneFile(File f) throws Exception {

POITextExtractor extractor = ExtractorFactory.createExtractor(f);

String extracted = extractor.getText();

return extracted;

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

if (args.length <= 0) {

System.err.println("ERROR: No filename specified.");

return;

}

for (String filename : args) {

File f = new File(filename);

System.out.println(extractOneFile(f));

}

}

}

Full Java 1.6 binaries are attached;

Apache POI license details apply.

Copy the ZIP archive to your TWiki server and unzip it in a directory of your choice.

With this tool in place, all we need to do is provide a stringifier plugin to

the add-on. This is done by adding a file called OpenXML.pm to the

lib/TWiki/Contrib/SearchEngineKinoSearchAddOn/StringifierPlugins

directory in the TWiki server installation:

# For licensing info read LICENSE file in the TWiki root. # This program is free software; you can redistribute it and/or # modify it under the terms of the GNU General Public License # as published by the Free Software Foundation; either version 2 # of the License, or (at your option) any later version. # # This program is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, # but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of # MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. See the # GNU General Public License for more details, published at # http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/gpl.html package TWiki::Contrib::SearchEngineKinoSearchAddOn::StringifyPlugins::OpenXML; use base 'TWiki::Contrib::SearchEngineKinoSearchAddOn::StringifyBase'; use File::Temp qw/tmpnam/; __PACKAGE__->register_handler( "application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.spreadsheetml.sheet", ".xlsx"); __PACKAGE__->register_handler( "application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document", ".docx"); __PACKAGE__->register_handler( "application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.presentationml.presentation", ".pptx"); sub stringForFile { my ($self, $file) = @_; my $tmp_file = tmpnam(); my $text; my $cmd = "java -jar /www/twiki/local/bin/openxmlextractor/openxmlextractor.jar '$file' > $tmp_file"; if (0 == system($cmd)) { $text = TWiki::Contrib::SearchEngineKinoSearchAddOn::Stringifier->stringFor($tmp_file); } unlink($tmp_file); return $text; # undef signals failure to caller } 1;This script assumes that the

openxmlextractor.jar helper is located at

/www/twiki/local/bin/openxmlextractor; you'll have to tweak this path to

reflect your local settings.

I haven't figured out yet how to correctly deal with encodings in the stringifier

code, so non-ASCII characters might not work as expected.

To verify local installation, change into /www/twiki/kinosearch/bin (this is

where my TWiki installation is, YMMV) and run the extractor on a test file:

./ks_test stringify foobla.docxAnd in a final step, enable index generation for Office documents by adding

.docx, .pptx and .xlsx to the Main.TWikiPreferences topic:

* KinoSearch settings

* Set KINOSEARCHINDEXEXTENSIONS = .pdf, .xml, .html, .doc, .xls, .ppt, .docx, .pptx, .xlsx

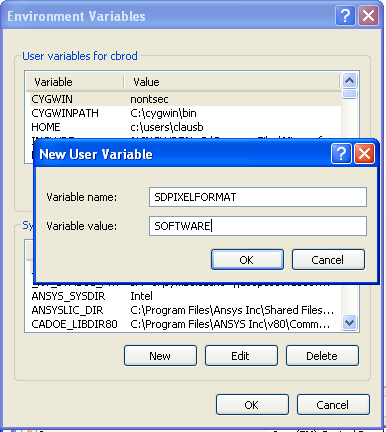

I'd rather take it nice and slow - disabling 3D acceleration in CoCreate Modeling (15 Jul 2009)

SDPIXELFORMAT, and give

it a value of SOFTWARE. To set the environment variable, use the System Control Panel.

Click sequence in Windows XP:

Click sequence in Windows XP:

- Start/Control Panel

- Run

Systemcontrol panel - Select the

Advancedtab - Click "Environment Variables".

- Start/Control Panel

- Click

System and Maintenance, thenSystem - Click

Advanced System Settings; this may pop up a user-access control dialog which you need to confirm - Click

Environment Variables

SDPIXELFORMAT and set the value to SOFTWARE.

Java-Forum Stuttgart (06 Jul 2009)

But the remaining few of us still had a spirited

discussion, covering topics such as dynamic versus static typing, various Clojure language

elements, Clojure's Lisp heritage, programmimg for concurrency, web frameworks, Ruby on Rails,

and OO databases.

To those who stopped by, thanks a lot for this discussion and for your interest.

And to the developer from Bremen whose name I forgot (sorry): As we suspected, there is

indeed an alternative syntax for creating Java objects in Clojure.

But the remaining few of us still had a spirited

discussion, covering topics such as dynamic versus static typing, various Clojure language

elements, Clojure's Lisp heritage, programmimg for concurrency, web frameworks, Ruby on Rails,

and OO databases.

To those who stopped by, thanks a lot for this discussion and for your interest.

And to the developer from Bremen whose name I forgot (sorry): As we suspected, there is

indeed an alternative syntax for creating Java objects in Clojure.

(.show (new javax.swing.JFrame)) ;; probably more readable for Java programmers (.show (javax.swing.JFrame.)) ;; Clojure shorthand

Common Lisp in CoCreate Modeling (20 Jun 2009)

Not many in the audience had heard about our project yet, so there were quite a few

questions after the presentation. Over all those years, we had

lost touch with the Lisp community a bit - so reconnecting to the CL matrix felt just great.

Not many in the audience had heard about our project yet, so there were quite a few

questions after the presentation. Over all those years, we had

lost touch with the Lisp community a bit - so reconnecting to the CL matrix felt just great.

Click on the image to view the presentation. The presentation mentions LOC (lines of code) data;

those include test code.

Previous posts on the European Lisp Symposium:

Click on the image to view the presentation. The presentation mentions LOC (lines of code) data;

those include test code.

Previous posts on the European Lisp Symposium:

- European Lisp Symposium

- Europan Lisp Symposium: Keynote

- European Lisp Symposium: Geeks Galore!

- Sightrunning in Milan

head replacement on Windows (16 Jun 2009)

lines = WScript.Arguments(0) Do Until WScript.stdin.AtEndOfStream Or lines=0 WScript.Echo WScript.stdin.ReadLine lines = lines-1 LoopThis is an extremely stripped-down version of head's original functionality, of course. For example, the code above can only read from standard input, and things like command-line argument validation and error handling are left as an exercise for the reader

Assuming you'd save the above into a file called

Assuming you'd save the above into a file called head.vbs, this is how you can

display the first three lines of a text file called someinputfile.txt:

type someinputfile.txt | cscript /nologo head.vbs 3Enjoy!

Sightrunning in Milan (12 Jun 2009)

Echt einfach, Alter! (09 Jun 2009)

European Lisp Symposium: Geeks Galore! (07 Jun 2009)

- Two days during which I didn't have to explain any of my T-shirts.

- Not having to hide my symptoms of internet deprivation on the first day of the symposium (when the organizers were still working on wifi access for everyone).

- Enjoying (uhm...) the complicated protocol dance involved in splitting up

a restaurant bill among five or six geeks. This is obviously something that

we, as a human subspecies, suck at

Special shout-outs go to Jim Newton,

Edgar Gonçalves, Alessio Stalla, Francesco Petrogalli and his friend Michele.

(Sorry to those whose names I forgot; feel free to refresh my memory.)

Special shout-outs go to Jim Newton,

Edgar Gonçalves, Alessio Stalla, Francesco Petrogalli and his friend Michele.

(Sorry to those whose names I forgot; feel free to refresh my memory.)

- Meeting Lisp celebrities like Scott McKay (of Symbolics fame)

- Crashing my hotel room with four other hackers (Attila Lendvai and the amazing dwim.hu crew) who demoed both their Emacs skills and their web framework to me, sometime after midnight. (Special greetings also to Stelian Ionescu.)

European Lisp Symposium 2009: Keynote (03 Jun 2009)

- "Any bozo can write code" - this is how David Moon dismissed Scott's attempt to back up one of his designs with code which demonstrated how the design was meant to work.

- "Total rewrites are good" - Scott was the designer of CLIM, which underwent several major revisions until it finally arrived at a state he was reasonably happy with.

- "If you cannot describe something in a spec, that's a clue!" - amen, brother!

- "The Lisp community has a bad habit of building everything themselves"

- "Immutability is good" (even for single-threaded code)

- "Ruby on Rails gets it right"; only half-jokingly, he challenged the community to

build something like "Lisp on Rails". Later during the symposium, I learned that

we already have Lisp on Lines

("LoL" - I'm not kidding you here

).

).

- "Java + Eclipse + Maven + XXX + ... is insane!" - and later "J2EE got it spectacularly wrong"

- He reminded us that the Lisp Machine actually had C and Fortran compilers, and that it was no small feat making sure that compiled C and Fortran programs ran on the system without corrupting everybody else's memory. (I'd be curious to learn more about this.)

- Lisp code which was developed during Scott's time at HotDispatch was later converted to Java - they ended up in roughly 10x the code size.

- The QRes system at ITA has 650000 lines of code, and approx. 50 hackers are working on it. Among other things, they have an ORM layer, transactions, and a persistence framework which is "a lot less complicated than Hibernate".

- Both PLOT and Alloy were mentioned as sources of inspiration.

- Should run on a virtual machine

- Good FFI support very important

- Support for immutability

- Concurrency and parallelism support

- Optional type checking, statically typed interfaces (

define-strict-function) - "Code as data" not negotiable

European Lisp Symposium 2009 (30 May 2009)

Other bloggers covering the event:

PS: While at lunch on Thursday, I had an interesting chat with a young

guy from Hasso-Plattner-Institut in Potsdam (Germany).

I was very impressed to hear about the many languages he already worked or experimented with.

Unfortunately, I completely forgot his name. So this is a shout-out to him:

If Google ever leads you here, I apologize for the brain leakage, and please drop

me a note!

Other bloggers covering the event:

PS: While at lunch on Thursday, I had an interesting chat with a young

guy from Hasso-Plattner-Institut in Potsdam (Germany).

I was very impressed to hear about the many languages he already worked or experimented with.

Unfortunately, I completely forgot his name. So this is a shout-out to him:

If Google ever leads you here, I apologize for the brain leakage, and please drop

me a note!

Speeding through the crisis (22 Apr 2009)

So I'm sticking to the old hardware, and it works great, except for one

thing: It cannot set bookmarks. Sure, it remembers which file I was playing

most recently, but it doesn't know where I was within that file. Without

bookmarks, resuming to listen to that podcast of 40 minutes length which

I started into the other day is an awkward, painstakingly slow and daunting task.

But then, those years at university studying computer science needed to

finally amortize themselves anyway, and so I set out to look for a software solution!

The idea was to preprocess podcasts as follows:

So I'm sticking to the old hardware, and it works great, except for one

thing: It cannot set bookmarks. Sure, it remembers which file I was playing

most recently, but it doesn't know where I was within that file. Without

bookmarks, resuming to listen to that podcast of 40 minutes length which

I started into the other day is an awkward, painstakingly slow and daunting task.

But then, those years at university studying computer science needed to

finally amortize themselves anyway, and so I set out to look for a software solution!

The idea was to preprocess podcasts as follows:

- Split podcasts into five-minute chunks. This way, I can easily resume from where I left off without a lot of hassle.

- While I'm at it, speed up the podcast by 15%. Most podcasts have more than enough verbal fluff and uhms and pauses in them, so listening to them in their original speed is, in fact, a waste of time. Of course, I don't want all my podcasts to sound like Mickey Mouse cartoons, of course, so I need to preserve the original pitch.

- Most of the time, I listen to technical podcasts over el-cheapo headphones in noisy environments like commuter trains, so I don't need no steenkin' 320kbps bitrates, thank you very much.

- And the whole thing needs to run from the command line so that I can process podcasts in batches.

#! /bin/bash

#

# Hacked by Claus Brod,

# http://www.clausbrod.de/Blog/DefinePrivatePublic20090422SpeedingThroughTheCrisis

#

# prepare podcast for mp3 player:

# - speed up by 15%

# - split into small chunks of 5 minutes each

# - recode in low bitrate

#

# requires:

# - lame

# - soundstretch

# - mp3splt

if [ $# -ne 1 ]

then

echo Usage: $0 mp3file >&2

exit 2

fi

bn=`basename "$1"`

bn="${bn%.*}"

lame --priority 0 -S --decode "$1" - | \

soundstretch stdin stdout -tempo=15 | \

lame --priority 0 -S --vbr-new -V 9 - temp.mp3

mp3splt -q -f -t 05.00 -o "${bn}_@n" temp.mp3

rm temp.mp3

The script uses lame,

soundstretch and

mp3splt for the job, so you'll have to download

and install those packages first. On Windows, lame.exe, soundstretch.exe and

mp3splt.exe also need to be accessible through PATH.

The script is, of course, absurdly lame with all its hardcoded filenames and parameters

and all, and it works for MP3 files only - but it does the job for me,

and hopefully it's useful to someone out there as well. Enjoy!

Reasons To Admire Lisp (part 1) (16 Apr 2009)

s_expression = atomic_symbol / "(" s_expression "."s_expression ")" / list

list = "(" s_expression < s_expression > ")"

atomic_symbol = letter atom_part

atom_part = empty / letter atom_part / number atom_part

letter = "a" / "b" / " ..." / "z"

number = "1" / "2" / " ..." / "9"

empty = " "

Now compare the above to, say,

Java.

(And yes, the description above doesn't tell the whole story since it doesn't cover any

kind of semantic aspects. So sue me.)

Oh, and while we're at it: Lisp Syntax Doesn't Suck,

says Brian Carper, and who am I to disagree.

So there.

mod_ntlm versus long user names (06 Mar 2009)

[Mon Mar 02 11:37:37 2009] [error] [client 42.42.42.42] 144404120 17144 /twiki/bin/viewauth/Some/Topic - ntlm_decode_msg failed: type: 3, host: "SOMEHOST", user: "", domain: "SOMEDOMAIN", error: 16The server system runs CentOS 5 and Apache 2.2. Note how the log message claims that no user name was provided, even though the user did of course enter their name when the browser prompted for it. The other noteworthy observation in this case was that the user name was unusually long - 17 characters, not including the domain name. However, the NTLM specs I looked up didn't suggest any name length restrictions. Then I looked up the mod_ntlm code - and found the following in the file

ntlmssp.inc.c:

#define MAX_HOSTLEN 32 #define MAX_DOMLEN 32 #define MAX_USERLEN 32Hmmm... so indeed there was a hard limit for the user name length! But then, the user's name had 17 characters, i.e. much less than 32, so shouldn't this still work? The solution is that at least in our case, user names are transmitted in UTF-16 encoding, which means that every character is (at least) two bytes! The lazy kind of coder that I am, I simply doubled all hardcoded limits, recompiled, and my authentication woes were over! Well, almost: Before reinstalling mod_ntlm, I also had to tweak its Makefile slightly as follows:

*** Makefile 2009/03/02 18:02:20 1.1 --- Makefile 2009/03/04 15:55:57 *************** *** 17,23 **** # install the shared object file into Apache install: all ! $(APXS) -i -a -n 'ntlm' mod_ntlm.so # cleanup clean: --- 17,23 ---- # install the shared object file into Apache install: all ! $(APXS) -i -a -n 'ntlm' mod_ntlm.la # cleanup clean:Hope this is useful to someone out there! And while we're at it, here are some links to related articles:

- http://blog.rot13.org/2005/11/mod_ntlm_and_keepalive.html

- http://twiki.org/cgi-bin/view/Plugins/TinyMCEPluginDev

to top

Edit | Attach image or document | Printable version | Raw text | Refresh | More topic actions

Revisions: | r1.1 | Total page history | Backlinks

Revisions: | r1.1 | Total page history | Backlinks

Blog

Blog